In these days of the 280-character tweet, it’s all too easy to get into a heated arguments with someone on the strength (or, far more often, weakness) of a ill-considered online blurt. I’ve done it myself. Our modern means of communication encourage instant feedback, often to the detriment of thoughtful reflection.

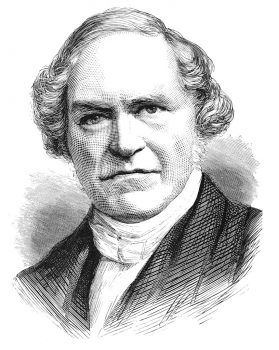

Less so in Darwin’s day. On 2nd January 1860, the mathematician, science historian, and polymath, William Whewell, wrote to Charles Darwin to acknowledge receipt of his copy of the first edition of ‘On the Origin of Species’:

My dear Mr Darwin

I have to thank you for a copy of your book on the ‘Origin of Species’. You will easily believe that it has interested me very much, and probably you will not be surprized to be told that I cannot, yet at least, become a convert to your doctrines. But there is so much of thought and of fact in what you have written that it is not to be contradicted without careful selection of the ground and manner of the dissent, which I have not now time for. I must therefore content myself with thanking you for your kindness.

believe me | Yours very truly | W Whewell

This seems to me the right way to go about things. Whewell—who is also an Anglican priest and theologian—disagrees fundamentally with Darwin’s revolutionary new theory, but is not prepared to dismiss it without more careful consideration.

I’m not sure how much careful consideration Whewell gave evolution by means of Natural Selection after his polite letter to Darwin. Not much, if their lack of subsequent correspondence is anything to go by. But at least Whewell had the decency to recognise Darwin had provided a lot of food for thought: a position worthy of the gentleman who coined the term scientist.

Whewell was by this time rather old, and probably, given his involvement in the Bridgewater Treatises, not disposed to adopt an undirected evolution of teleological processes. But one has to appreciate the civility of his tone.

Whewell possibly suspected that the origin of species lay at a deeper level than he found in Darwin’s book (now known to occur in RNA and DNA). Whewell was a lifelong opponent of Darwin’s empirical approach to research, the process of testing any hypothesis by using direct or indirect observations and experience. It is impossible to express as well as him the greater value of inductive processes, as regards facts and theories.

" We have seen", he says, "that there are propositions which are known to be necessarily true, and that such knowledge is not and cannot be obtained by mere observation of actual facts. It has been shown also that these necessary truths are the results of certain fundamental ideas, such as those of space, time, number, and the like.

Hence it follows inevitably that these ideas and others of the same kind are not derived from experience. For these ideas possess a power of infusing into their developments that very necessity which experience can in no way bestow. This power they do not borrow from the external world, but possess by their own nature. Thus, we unfold out of the idea of space, the propositions of geometry, which are plainly truths of the most rigorous necessity and universality. But if the idea of space were merely collected from observation of the external world, it could never enable or entitle us to assert such propositions: it could never authorise us to say that not merely some lines but all lines not only have but must have those properties which geometry teaches. Geometry in every proposition speaks a language which experience never dares to utter, and indeed of which she but half comprehends the meaning. Experience sees that the assertions are true, but she sees not how profound and absolute Is their truth." Phil i. 71.

"Experience," says Mr. Whewell, "must always consist of a limited number of observations; and however numerous these may be, they can show nothing with regard to the infinite number of cases in which the experiment has not been made. . . . Truths can only be known to be general, not universal, if they depend upon experience alone. Experience cannot bestow that universality which she herself cannot have, nor that necessity of which she has no comprehension." Phil. i. 60, 61.

" We do not," as Mr. Whewell most justly remarks "acquire from mere observation —a right to assert that a proposition is true in all cases." But that we do possess the propensity is clear from this, that we generalize the abstract suggestion of mistaken relations, if of frequent occurrence, as readily as of true ones, nor ever dream of abandoning our conclusions till their inconsistency with further observation stares us in the face.”