Charles Darwin finally went public with his theory of evolution by means of Natural Selection on 1st July 1858. His friends Joseph Dalton Hooker and Charles Lyell had arranged for a hastily compiled collection of papers to be read at the Linnean Society of London. The death of his infant son three days earlier prevented Darwin from attending.

Lyell in particular had encouraged Darwin to publish his ideas as soon as possible, perhaps fearing his friend might be scooped. Two years earlier, after almost two decades’ research, Darwin had finally begun writing his ‘big species book’. But Darwin’s plans for his magnum opus went out the window when he received a letter from Alfred Russel Wallace, who was collecting specimens in the Malay Archipelago. Wallace’s letter included a paper describing a theory uncannily similar to Darwin’s own.

At this point, conspiracy theorists are in the habit of claiming Darwin did the dirty on Wallace by going quickly to press before Wallace could return to Britain. Some have even gone so far as to suggest Darwin stole Wallace’s idea: an allegation most charitably described as bullshit.

Darwin was devastated by Wallace’s letter. He immediately forwarded Wallace’s paper to Lyell, indicating he felt honour-bound to see it published. But he was understandably reluctant not to receive due credit for the theory he had been working on for 20 years. A week later, in response to a reply from Lyell (now lost) Darwin explained:

There is nothing in Wallace’s sketch which is not written out much fuller in my sketch copied in 1844, & read by Hooker some dozen years ago. About a year ago I sent a short sketch of which I have copy of my views (owing to correspondence on several points) to Asa Gray, so that I could most truly say & prove that I take nothing from Wallace. I shd. be extremely glad now to publish a sketch of my general views in about a dozen pages or so. But I cannot persuade myself that I can do so honourably. Wallace says nothing about publication, & I enclose his letter.— But as I had not intended to publish any sketch, can I do so honourably because Wallace has sent me an outline of his doctrine?— I would far rather burn my whole book than that he or any man shd. think that I had behaved in a paltry spirit. Do you not think his having sent me this sketch ties my hands? I do not in least believe that that [sic] he originated his views from anything which I wrote to him.

If I could honourably publish I would state that I was induced now to publish a sketch (& I shd be very glad to be permitted to say to follow your advice long ago given) from Wallace having sent me an outline of my general conclusions.— We differ only, that I was led to my views from what artificial selection has done for domestic animals. I could send Wallace a copy of my letter to Asa Gray to show him that I had not stolen his doctrine. But I cannot tell whether to publish now would not be base & paltry: this was my first impression, & I shd. have certainly acted on it, had it not been for your letter.

This is a trumpery affair to trouble you with; but you cannot tell how much obliged I shd. be for your advice.—

By the way would you object to send this & your answer to Hooker to be forwarded to me, for then I shall have the opinion of my two best & kindest friends.— This letter is miserably written & I write it now, that I may for time banish whole subject. And I am worn out with musing.

…or, to paraphrase in more succinct modern parlance:

HELP!! Can you and Hooker think of any way I can do the right thing by Wallace, and still take some credit for my theory, without it all looking a bit grubby?

Several letters passed back and forth between the three friends, some of them now lost (thereby providing fodder for the conspiracy theorists). But, reading between the missing lines, it seems Hooker suggested there was no need for Darwin’s hard work to go unrecognised, nor for him to dash off a new paper. Instead, Darwin’s 1844 sketch and his copy of the letter he sent to Asa Gray could be presented alongside Wallace’s paper. The Linnean Society seems to have been chosen as the forum for the ‘joint’ papers because, as a fellow of the society, Hooker was entitled to submit papers for presentation and subsequent publication. The submission was rushed through as hastily as it was because the society was about to hold its final meeting of the season.

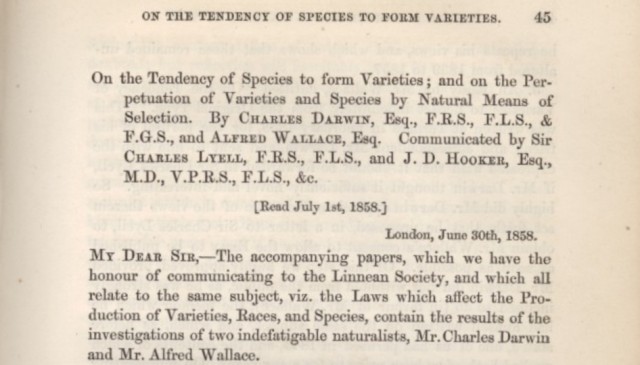

The papers were read at the Linnean Society on 1st July 1858 under the snappy title: On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection.

In their letter introducing Darwin and Wallace’s papers, Lyell and Hooker explained:

These gentlemen having, independently and unknown to one another, conceived the same very ingenious theory to account for the appearance and perpetuation of varieties and of specific forms on our planet, may both fairly claim the merit of being original thinkers in this important line of inquiry; but neither of them having published his views, though Mr. Darwin has for many years past been repeatedly urged by us to do so, and both authors having now unreservedly placed their papers in our hands, we think it would best promote the interests of science that a selection from them should be laid before the Linnean Society.

It seems clear from this introduction that Hooker and Lyell’s primary concern was not so much to ‘best promote the interests of science’ (which, after 20 years, surely could have waited a bit longer), but to establish their friend’s claim to (at very least) equal scientific priority with Wallace. But good for them! They knew Darwin deserved credit, and they made sure he received it.

And what was the reaction of the good fellows of the Linnean Society after hearing this revolutionary, godforsaken, paradigm-shifting theory read out on 1st July? Almost nothing. A few people made passing comment on the joint papers, but they were otherwise pretty much a damp squib. Indeed, the following May, the President of the Linnean Society, Thomas Bell, famously remarked:

The year which has passed […] has not, indeed, been marked by any of those striking discoveries which at once revolutionize, so to speak, the department of science on which they bear;

With hindsight, something of a howler, Mr Bell!

The shock of nearly being scooped spurred Darwin into action. A couple of days after the papers were presented, he set aside his ‘big species book’ and began to write a short ‘abstract’ of it. He was never to complete his big book. The abstract was eventually to grow to book size, and was published the following year under the title On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life.

How did Wallace feel about the publication, without his prior knowledge, of his paper alongside Darwin’s? His immediate response to Hooker on being told the news was ‘gratification’. In a letter to a friend shortly afterwards, he described himself ‘a little proud’. Throughout the remainder of his long life, he continued to express complete satisfaction at what had happened. Indeed, in an article written in 1903, Wallace modestly suggested he had received too much credit:

[M]y connection with Darwin and his great work has helped to secure for my own writings on the same questions a full recognition by the press and the public; while my share in the origination and establishment of the theory of Natural Selection has usually been exaggerated. The one great result which I claim for my paper of 1858 is that it compelled Darwin to write and publish his Origin of Species without further delay. The reception of that work, and its effect upon the whole scientific world, prove that it appeared at the right moment; and it is probable that its influence would have been less widespread had it been delayed several years, and had then appeared, as he intended, in several bulky volumes embodying the whole mass of facts he had collected in its support. Such a work would have appealed to the initiated few only, whereas the smaller volume actually written was read and understood by the educated classes throughout the civilised world.

Well said, Mr Wallace! Thank you for being so decent. And thank you for unwittingly jolting Mr Darwin into writing the most important book in the history of biology.

Acknowledgement: This article was informed by the excellent book Dispelling the Darkness: Voyage in the Malay Archipelago and the Discovery of Evolution by Wallace and Darwin by John van Wyhe. [ISBN 978–981–4458–80–1]