12th February, 2026.

Dear Friend of Darwin,

Charles Darwin was born 217 years ago today. Happy Darwin Day!

The more I read of Darwin’s life and work, the more it’s brought home to me that evolution by means of natural selection is not all cheetahs versus gazelles, fish dragging themselves out of the ocean, and monkeys walking upright. It’s far more subtle and ubiquitous than that. Darwinian evolution sweats the small stuff. It fine-tunes. It tinkers with the details. So did Charles Darwin.

Darwin studied barnacles, coral polyps, bees, earthworms, pigeons and domestic poultry—not exactly headline acts. But where he really shone was in his studies of the plant kingdom. On the quiet, Darwin was one hell of an amateur botanist. He studied how plants manage to disperse their seeds over vast distances; how they move; and how some trap and digest insects as food. He studied the pros and (mostly) cons of plant self-fertilisation; how flowers attract and exploit pollinators; and the measures they take to increase the likelihood of cross-pollination.

Darwin’s animal and plant studies weren’t so esoteric as they might seem: they all furthered his argument that cumulative slow change guided by natural selection shaped the natural world.

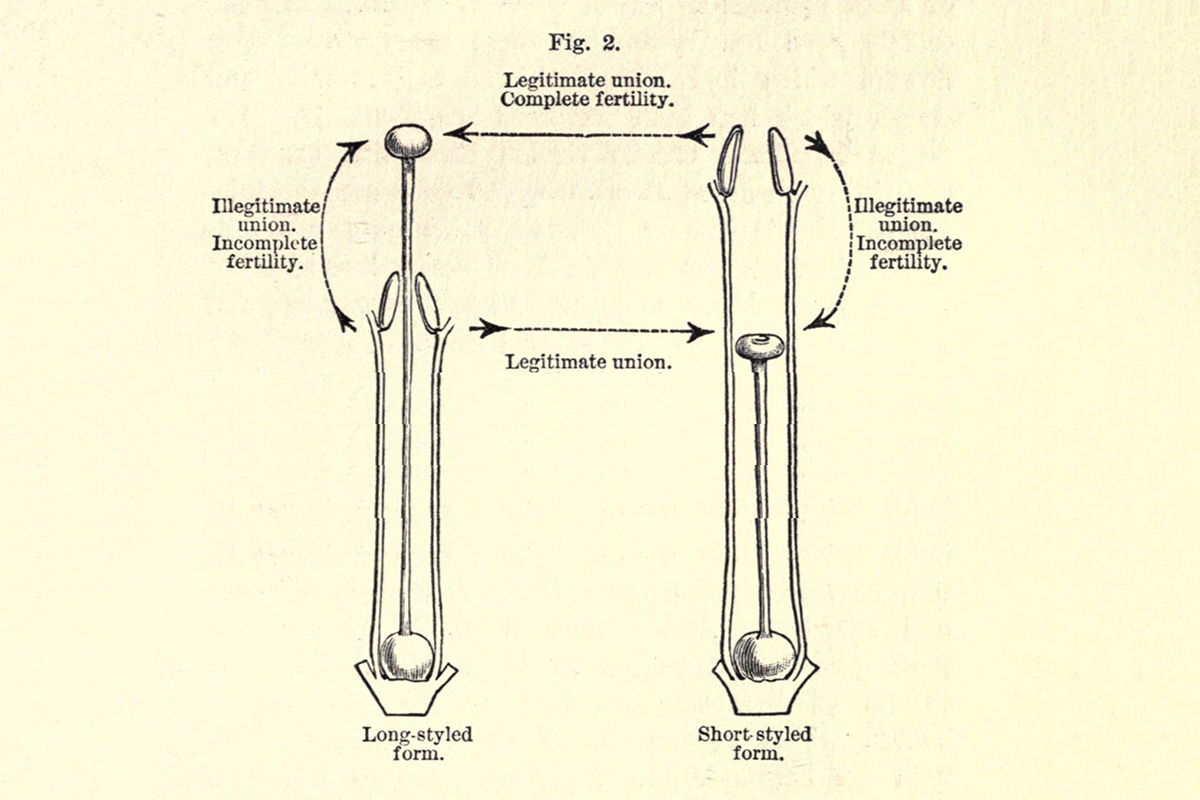

You and I, if we were phenomenally observant, might notice that certain species of flowers have more than one arrangement of male stamens and female pistils: sometimes the stamens are longer than the pistils, sometimes the reverse is true. If we were particularly inquisitive, we might even think, Oh, that’s interesting; I wonder why that might be. Charles Darwin noticed this very phenomenon (nowadays known as heterostyly) and ended up heading down a research rabbit-hole, writing three scientific papers followed by an entire book on the subject. This seemingly trivial detail was, he realised, yet another compelling example of natural selection in action: heterostyly helped promote cross-pollination between flowers of the two different forms and hinder it between flowers of the same form (and, hence, self-pollination). It boiled down to where precisely pollen was deposited on, and received from, the bodies of visiting insects.

Taken from The Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species by Charles Darwin.

…Talk about sweating the small stuff and fine-tuning! But, as Darwin wrote in his autobiography:

no little discovery of mine ever gave me so much pleasure as the making out the meaning of heterostyled flowers

Darwin gave us a wonderful, better new way to look at the natural world. Keep your eyes open, stay inquisitive, and, when you notice some small, interesting detail out there, ask yourself, What might Darwin say?

Natural selection

A couple of books you might enjoy concerning Darwin’s apparently esoteric research:

Darwin’s Most Wonderful Plants by Ken Thompson

An examination of each of Darwin’s major works on plants. The subject matter includes orchids, climbing plants, insectivorous plants, plant domestication, and plant movement.

Darwin’s Backyard by James T Costa

An exploration of Charles Darwin the experimenter. Find out how and why Darwin carried out his long-term experimental research programme into such diverse topics as: barnacles, the dispersal mechanisms of plants, and the intelligence and actions of earthworms.

Missing links

Some Darwin-related articles you might find of interest:

- The importance of Charles Darwin’s documentary archive has been recognised by its inclusion on the UNESCO International Memory of the World Register. The Darwin Archive comprises documents held at Cambridge University Library, the Natural History Museum in London, the Linnean Society of London, Darwin’s former home at Down House in Kent, the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, and the National Library of Scotland.

- Podcast episode: The History of Revolutionary Ideas: Darwin.

David Runciman talks to geneticist and science writer Adam Rutherford about the book that fundamentally altered our understanding of just about everything: Darwin’s On The Origin of Species. - Video: Darwin’s unexpected final obsessionwith earthworms.

- Darwin Online has published Charles Darwin’s address book. Here’s their introduction, and here’s the address book.

- The University of Edinburgh recently completed a five-year programme to catalogue, preserve, and enhance access to the Charles Lyell Collection. Geologist Lyell was a close friend of Darwin, and major influence on his work. Here’s the collection’s snazzy new website.

- Leonard Jenyns on the variation of species and Charles Darwin on the origin of species 1844–1860

At the 1856 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Rev. Leonard Jenyns (1800−1893) delivered one of the most significant statements on the nature and the origin of species in the years immediately preceding Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Jenyns was a long-standing friend of Darwin and had turned down the place aboard HMS Beagle subsequently taken by Darwin. - The November 2025 issue of the journal Paleobiology contained a collection of papers exploring Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould’s 1972 paper on punctuated equilibria, in which they argued that species don’t always evolve through slow, steady change. Instead, the fossil record shows long periods in which species remain remarkably stable, interrupted by relatively brief bursts of evolutionary innovation linked to the origin of new species. The Paleobiology papers include a retrospective review of the importance of the idea of punctuated equilibria, and Niles Eldredge’s personal reflections.

- Talking of brief evolutionary bursts, a recent paper finds that most living species derived from large groups which evolved in relatively short periods of time; or, as they put it, rapid radiations underlie most of the known diversity of life.

- Talking even more of evolutionary bursts, another recent study suggests changes in solar energy fuelled high speed evolutionary changes 500-million years ago. (See also the original journal paper Orbitally‐driven nutrient pulses linked to early Cambrian periodic oxygenation and animal radiation.)

- The case for subspecies—the neglected unit of conservation

To lump or to split? Deciding whether an animal is a species or subspecies profoundly influences our conservation priorities. (See also my old post Lumpers v Splitters.) - Sexual selection in beetles leads to more rapid evolution of new species, long-term experiments show

40 years of experiments following 200 generations of beetles show the importance of sexual selection in the emergence of new species. (See also the original journal paper: The effects of sexual selection on functional and molecular reproductive divergence during experimental evolution in seed beetles.) - Why did life evolve to be so colourful? Research is starting to give us some answers

If evolution had taken a different turn, nature would be missing some colours. - Some of the biggest fossils Darwin sent home from the Beagle voyage were those of extinct giant ground sloths, Megatherium and Mylodon. Scientists have figured out how extinct giant ground sloths got so big and where it all went wrong.

- Large brains and manual dexterity are both thought to have played an important role in human evolution. A new study has found that primates with longer thumbs tend to have bigger brains, suggesting the brain co-evolved with manual dexterity. (See also the original journal paper Human dexterity and brains evolved hand in hand.)

- Thumbs and brains are all well and good, but paleoanthropologist John Hawks explores another human characteristic that remains an enduring evolutionary enigma: what the heck are chins for?

Journal of researches

Progress on my book Through Darwin’s Eyes has remained slow but steady. I’m currently about half-way through the second draft.

A minor recurring themes in the book is Darwin’s tendency to scope-creep. When he embarked on a new project, it inevitably grew and grew. One example, as we have already seen, was his research into heterostyly. Another was his barnacle work, which began as a short project to describe a few barnacles to establish his credentials as ‘a species man’, but which ended up as an eight-year, four-book study of every known species of barnacle, both living and extinct. Similarly, Darwin only originally intended to include his thoughts on human evolution in a single chapter tagged on to the end of his book The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication, but the work soon expanded into two separate books in their own right: The Descent of Man and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Darwin liked to be thorough.

Somewhat ironically, I recently decided I needed to give more coverage in my book to Darwin’s work on heterostyly, which will require me to write another, unplanned chapter. I like to think Darwin would have approved.

Expression of emotions

Thanks as always for reading this newsletter. If you enjoyed it, please share it with your friends—and politely suggest they might like to subscribe to receive their own free copy.

See you next time!

Richard Carter, FCD

friendsofdarwin.com

richardcarter.com

Places to follow me:

Friends of Charles Darwin: Blog • Newsletter • Reviews • Articles • RSS

Personal: Blog • Newsletter • Reviews • Moor book • Darwin book • RSS

Social: Bluesky • Mastodon • Substack • Instagram

Leave a Reply