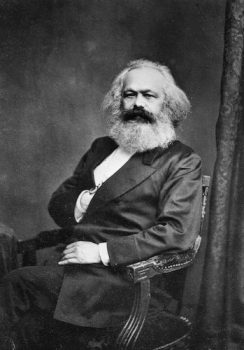

It’s a well-known chestnut of Darwinian trivia that the father of international socialism, Karl Marx, once offered to dedicate one of the volumes of his magnum opus, Das Kapital, to that other 19th Century bearded revolutionary living in the south of England, Charles Darwin.

Unfortunately, it turns out this particular chestnut is something of a myth, although the story of how it came about is of interest in its own right. It seems to have begun thanks to the following quote:

Dear Sir:

—Letter from Charles Darwin to Karl Marx

I thank you for the honour which you have done me by sending me your great work on Capital; & I heartily wish that I was more worthy to receive it, by understanding more of the deep and important subject of political Economy. Though our studies have been so different, I believe that we both earnestly desire the extension of Knowledge, & that this is in the long run sure to add to the happiness of Mankind.

I remain, Dear Sir

Yours faithfully,

Charles Darwin

October, 1873

Marx genuinely admired Darwin’s Origin, despite its ‘crude English style’. He even sent Darwin a personally inscribed copy of the recently published second edition of Das Kapital in 1873. Darwin’s letter of acknowledgment (quoted above) delighted Marx, who used it as proof that the great scientist appreciated his work. In fact, Darwin, ever the gentleman (and no German scholar), was merely being polite: he never read Marx’s book, the vast majority of whose pages remained uncut in his library.

But, although Marx admired Darwin’s work, some of its implications, particularly the support it gave to the theories of Thomas Malthus, gave him great cause for concern. This makes it extremely unlikely that Marx would ever have considered dedicating Das Kapital to Darwin.

So, how did the dedication story come about? The answer is given, amongst other places, in Francis Wheen’s highly readable biography, Karl Marx (Fourth Estate, ISBN: 1-85702-637-3). It all started with a second Darwin letter unearthed amongst Marx’s papers, dated 13th October, 1880:

Dear Sir:

I am much obliged for your kind letter & the Enclosure.— The publication in any form of your remarks on my writing really requires no consent on my part, & it would be ridiculous in me to give consent to what requires none. I shd prefer the Part or Volume not to be dedicated to me (though I thank you for the intended honour) as this implies to a certain extent my approval of the general publication, about which I know nothing.— Moreover though I am a strong advocate for free thought on all subjects, yet it appears to me (whether rightly or wrongly) that direct arguments against christianity and theism produce hardly any effect on the public; & freedom of thought is best promoted by the gradual illumination of men’s minds, which follow from the advance of science. It has, therefore, always been my object to avoid writing on religion, & I have confined myself to science. I may, however, have been unduly biased by the pain which it would give some members of my family, if I aided in any way direct attacks on religion.— I am sorry to refuse you any request, but I am old & have very little strength, and looking over proof-sheets (as I know by present experience) fatigues me much.

I remain Dear Sir,

Yours faithfully,

Ch. Darwin

This letter was published in a Soviet newspaper in 1931, which went on to suggest that the enclosures referred to in the letter might have been chapters from Das Kapital that dealt with evolution. No matter that Das Kapital, a book on economics, could never be considered a direct attack on religion, whatever Marx’s well-documented views on the subject.

So what on Earth was going on?

The mystery was investigated and solved by Margaret Fay of the University of California, who came across an obscure book published in 1881, entitled The Students’ Darwin. This was the second in a series of books sponsored by a pair of evangelical atheists.

The author of the book, Edward Aveling, later became the lover of Marx’s daughter, Eleanor. In 1895, he and Eleanor began organising her late father’s papers (which she had recently inherited from Engels). Later, in 1897, Aveling wrote an article about Marx and Darwin, in which he mentioned having corresponded with Darwin. Presumably, he then filed Darwin’s letter to him along with Marx’s papers.

Eventually, a letter from Aveling to Darwin (dated 12th October, 1880) was discovered amongst Darwin’s papers at Cambridge University. Enclosed with this letter were sample chapters from The Students’ Darwin. The letter requested permission to dedicate the book to Darwin.

So, it wasn’t Karl Marx’s Das Kapital that Darwin politely declined the dedication of; it was Edward Aveling’s The Students’ Darwin.

I must admit to having experienced a certain degree of disappointment on learning that the famous Das Kapital dedication chestnut was a myth. On reflection, however, I like to think that Darwin would have approved of the sort of reasoning that questioned a cherished long-standing belief, and of the search for literary missing links that eventually led to the truth. That’s what science and historical research are all about.

Leave a Reply